In English below.

Nu sitter vi här igen, på Primary Children’s Hospital, Edith och jag. Eller ja, Edith ligger i sjukhussängen under en grå filt och jag sitter bredvid i en fåtölj med gungfunktion. Edith har 13 elektroder i huvudet som är inlindat i flera lager bandage. Jag har min FIRESfighter-keps på mitt, tusen tankar i det, men känner mig ändå ganska tom. Edith och jag tillbringade ett par nätter på samma sätt sommaren 2021, då som nu väntade vi på anfall. Då minns jag att jag skrev ett inlägg om den smygande nattsjuksköterskan, jag minns bara rubriken och att hon helt plötsligt kunde stå inne i rummet med ett leende under munskyddet utan att jag hört henne gå in. Det är andra sköterskor i natt, men de verkar också bra.

Operationen där elektroderna implanterades gick som planerat, inga blödningar och inga andra komplikationer. Även om riskerna inte är stora statistiskt sett, så finns de ändå där. Både narkos och kirurgi innebär alltid en risk. Som förälder till ett barn som ska sövas och opereras är ett par procents risk på tok för mycket för att man inte ska känna oron gnaga, tvivlen spöka. En del av mig ville rymma iväg med Edith från operationsförberedelserna, åka hem till Sverige och låtsas att allt skulle bli bra ändå, men det blir det inte. Vi måste utsätta vår dotter för den här undersökningen för att ge henne en chans att få ett liv, det är enda chansen.

I skrivande stund, onsdagen den 20 september kl 00.30 SLC-tid, dvs kl 8.30 i Sverige, har vi bara registrerat ett anfall. Med Tysklandsbesöket efter midsommar, där Edith fastnade i något som liknande status epilepticus i flera dagar, i färskt minne, är vi oroliga för alltför drastiska medicinjusteringar. Vi får väga riskerna mot kostnaderna som varje extra dygn på sjukhuset innebär. Edith kommer alltid först, men vi måste ta hänsyn till ekonomin också, vi kan inte tillbringa en vecka på sjukhuset för den här undersökningen, det spräcker budgeten, den är redan svår att hantera och de första räkningarna är redan här.

Som svensk hade jag aldrig trott att jag skulle behöva ta ekonomisk hänsyn när det gäller livsavgörande vård för mitt barn, det är nog svåra beslut och utmaningar ändå. Men så är den krassa verkligheten när det gäller Ediths kamp, allt annat vore omskrivningar och lögn. Eftersom svensk hälso- och sjukvård inte erbjuder något alternativ och inte vill eller tycker sig kunna samarbeta fullt ut med amerikanerna på grund av formalia, står vi själva. Vi står utan stöd i besluten, utan ekonomisk uppbackning, utan försäkringar om komplikationer tillstöter. Jag har svårt att acceptera den svenska hållningen, främst kanske för att jag är Ediths pappa, men också därför att jag tycker att den inte håller intellektuellt, etiskt eller moraliskt. Skulle vi neka ett inflyttat amerikanskt barn med en RNS hjälp? Skulle vi neka någon som fått problem efter en plastikresa till ett land vi inte har vårdavtal med, vård vid hemkomst? Skulle vi neka en flykting med en protes vi inte använder i Sverige stöd, om den behövde justeras?

Alldeles oavsett vad den svenska epilepsiexpertisen tycker om mitt och Ediths mammas beslut att ta Edith till USA för att operera in en RNS för två år sedan, så kvarstår det faktum att Edith är deras patient, oskyldig till valet av behandlingsmetod. Alldeles oavsett kvarstår faktum att det inte, hittills, erbjudits ett alternativ eftersom den svenska verktygslådan är tom. Jag kanske är orättvis i min beskrivning, jag kanske är för partiskt, jag har kanske helt eller delvis fel, jag vet inte säkert längre. Men om jag huvudsakligen har rätt, så är avsaknaden av bilaterala avtal mellan Sverige och USA ganska klena argument när det kommer till ett barns liv. Ett barn som drabbats av en diagnos som drabbar en på miljonen passar per definition inte in i ett standardiserat vårdförlopp, då krävs undantag som, om man så vill, bekräftar de vanliga reglerna.

Man får ta seden dit man kommer och vi anpassar oss efter det amerikanska systemet som är uppbyggt kring försäkringar och välgörenhet, istället för skattefinansiering. För den som saknar försäkringar innebär det att räkningarna måste betalas ur egen ficka. Så är det för oss och då måste vi helt enkelt väga kostnader mot risker. Trots enormt engagemang av Dr Bollo, generösa rabatter och en vilja att dra ner på kostnader där det går, från läkarna och sjukhuset här i SLC, så balanserar vi på gränsen till vad vi klarar av. Därför måste vi nog sänka medicinerna ytterligare imorgon om inte anfallen kommer snart, även om vi egentligen inte vill.

FIRESfighterEdith on Instagram

http://youtube.com/@FIRESfighterEdith

In English.

Waiting for seizures and the lack of bilateral agreements

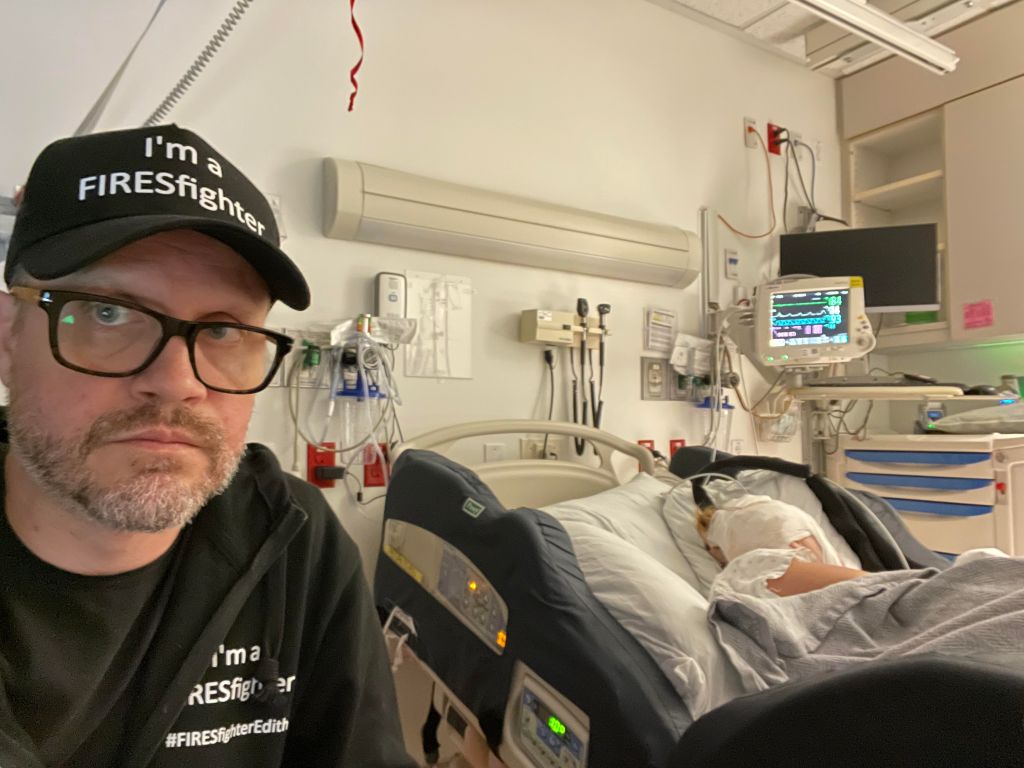

Now we are sitting here again, at Intermountain Primary Children’s Hospital in SLC, Edith and I. Or to be precise, Edith is lying in the hospital bed under a gray blanket and I’m sitting next to it in an armchair with a rocking function. Edith has 13 EEG electrodes in her head, which is wrapped in several layers of bandages. I have my FIRESfighter cap on my head, a thousand thoughts in it, but still I feel quite empty. Edith and I spent a couple of nights in the same way in the summer of 2021, then as now we were waiting for seizures. Then I remember that I wrote a post about the whispering night nurse, I just remember the title and that all of a sudden she could stand in the room with a smile under the mask without my hearing her enter . There are different nurses tonight, but they seem just as good.

The operation where the electrodes were implanted went as planned, no bleeding and no other complications. Although the risks are not statistically significant, they are still there. Both anesthesia and surgery always involve a risk. As a parent of a child who is to be sedated and operated on, a couple of percent risk is too much for you not to feel the worries gnawing, the doubts haunting you. Part of me wanted to run away with Edith from the surgery preparations, go home to Sweden and pretend that everything would be fine anyway, but it won’t be. We must subject our daughter to this examination to give her a chance at a life, it is our only hope.

At the time of writing this post, on Wednesday September 20th at midnight SLC time, i.e. at 8 AM in Sweden, we have only registered one seizure. With the visit to Germany at midsummer, where Edith got stuck in some kind of status epilepticus for several days, fresh in our minds, we are worried about too drastic medication adjustments. We have to weigh the risks against the costs that every extra day in the hospital entails. Edith always comes first, but we have to consider our finances too, we can’t spend a week in the hospital for this examination, it’s bursting our budget, it’s already hard to manage and the first bills are already here.

As a Swede, living in socialized Sweden, I never thought I would have to take financial considerations into account when it comes to vital care for my child, there are enough difficult decisions and challenges anyway. But such is the reality of Edith’s fight, to say otherwise would be paraphrasing and lying. Since Swedish healthcare does not offer any alternative treatment and does not want or considers itself able to cooperate fully with the Americans, according to practice, we are on our own. We stand without support from Sweden in the difficult decisions, without financial backing, without insurance if complications arise. I find it difficult to accept the Swedish decision not to support Edith’s fight, mainly perhaps because I am Edith’s father, but also because I think it does not hold intellectually, ethically or morally. Should Sweden deny an immigrated American child with an RNS help? Would Swedish healthcare deny someone who had problems after a plastic surgery trip to a country we do not have a care agreement with, care upon return? Would we say to a refugee with a prosthesis we don’t use in Sweden: sorry but you have to deal with this yourself?

Regardless of what the Swedish epilepsy experts think about my decision and Edith’s mother’s decision to take Edith to the USA to start RNS-treatment two years ago, the fact remains that Edith is their patient, innocent of the choice of treatment method. Regardless, the fact remains that they have not, so far, presented an alternative treatment. I may be unfair in my description, I may be too biased, I may be completely or partially wrong, I don’t know for sure anymore. But if I’m mainly right, then the lack of bilateral healthcare agreements between Sweden and the US is a pretty weak argument for not acting when it comes to a child’s life. A child affected by a diagnosis that affects one in a million does not, by definition, fit into a standardized process of, then exceptions are required that, if you will, confirm the usual rules.

As foreigners in the USA, we of course accept the American system which is built around healthcare insurance. For those without insurance, this means that the bills must be paid out of their own pocket. That’s how it is for us and then we simply have to weigh costs against risks. Despite the absolutely fantastic commitment of Dr. Bollo, generous discounts and a willingness to cut costs wherever possible from the doctors and Primary Children’s Hospital here in SLC, we are balancing on the edge of what we can handle. Therefore, we will probably have to lower the medication further tomorrow if the seizures don’t come soon, even if that scare us andvwe don’t really want to.

/Edith´s father Carl

More information about Edith´s journey

FIRESfighterEdith on Instagram

http://youtube.com/@FIRESfighterEdith

#FIRESfighterEdith #Epilepsy #Epilepsi